~Balanced academic orbit

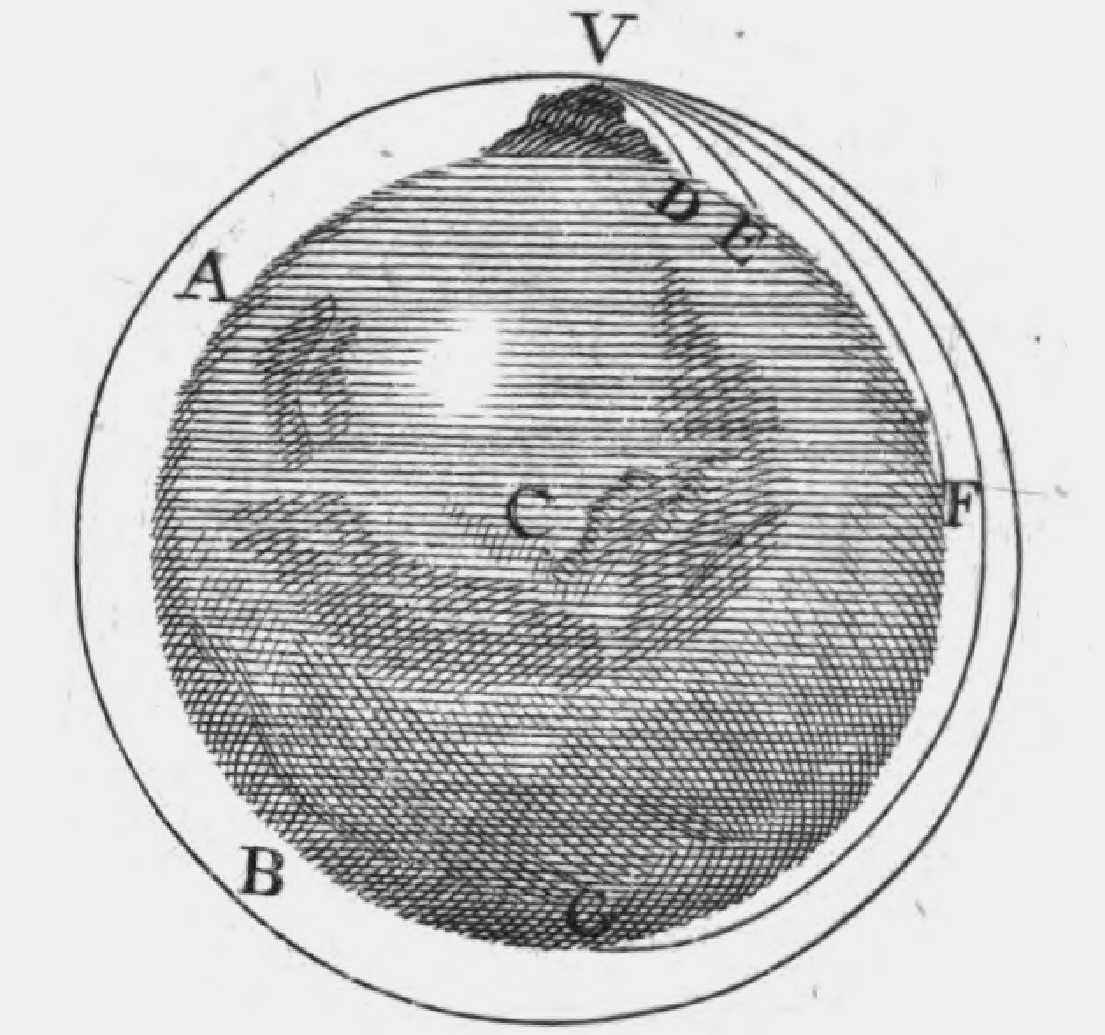

What is the difference between flight and orbit? Flight is a never-ending fight against gravity. It requires consistent effort to sustain. Given a finite fuel source, landing becomes inevitable. In contrast, orbit uses gravity to its advantage—falling only spurs you forward. Progress becomes essentially inevitable.

Until now, my long-term work pattern has been like a series of flights—at times intense, but ultimately unsustainable. I have demonstrated I have the fuel capacity to carry out long-haul courses of study and research. But no matter how much fuel I start with, it eventually runs out, after which I need to come back down to Earth to recover and prepare for the next launch.

One of my grad school goals is to reach academic orbit—a state of sustained free-fall, where I’m supported by expertise, networks, and habits that make daily progress the default despite the challenges of research and the distractions that come along with being an academic. From there, over the weeks, months, and years of the rest of my career, I can make steady, unrelenting progress on my ambitious research goals of tackling challenging problems facing the future of civilisation.

This concept of ‘academic orbit’ comes from Alkjash’s essay on the gravity turn. Alkjash’s essay focusses on certain specific aspects of academic orbit: established researchers have a history of successful publications that generate sequels and applications; a network of capable collaborators that share research ideas; the reputation to draw in grad students and postdocs to grow their research program year by year; and the context and resources to frequently attend conferences to keep up-to-date on the latest developments in the field.

In my experience, there appears to be another important element of sustainable research that is not discussed in that essay: achieving a balance between investing for the short-term versus the long-term. In the intense race against one project deadline after another that characterises flight, it’s all too easy to spend all of my time in the most short-term relevant activity (coding, running experiments, writing papers, depending on the week). In contrast, it seems impossible to save time for activities like the following.

Staring into the abyss. Asking myself the Hamming questions. Analysing the path to impact for my work. Thinking it through, or rethinking it in light of newly-discovered limitations or barriers. Deciding when to pivot to a new approach, or a new problem altogether.

Drinking from the firehose. Monitoring developments relevant to my field. In AI, this means paying (the right amount of) attention to the dizzying array of developments announced by academia and industry, while being careful to filter out the noise and update only on the signal.

Climbing the shoulders of giants, or, even, of the giant tower of regular-sized people that is the accumulated extent of human knowledge. Practicing the virtue of scholarship, and even just building out an antilibrary so I know where to look if I need something specific.

Being a person. A person who lives in a body that needs nutrition, exercise, and sleep. A person who needs to take a break once in a while after a period of intense effort. A person in a community of family and friends who have acted as an extremely supportive fuel source for each flight, and occasionally need my support in turn.

I can recognise all of these activities as vitally important to my long-term career goals. They are what enables me to select more important and intellectually challenging research projects, rather than just pursuing incremental progress in fashionable directions. They are what enables me to do a better job on each individual project, and create work of lasting value rather than work that just meets the bar.

Yet, I have historically underinvested in these activities. When I do get time to do these things, it’s usually between flights, when I’m burnt out and don’t have the energy to make meaningful progress on these goals. This is not surprising—these activities are existentially, intellectually, physically, and socially challenging in themselves!

In contrast, I notice my academic role models consistently defend time for these kinds of activities, be it on a daily, weekly, or yearly basis. Maybe they put these aside for an important deadline or trip. Or, maybe, what a thought! they might put aside the deadline or the trip instead.

My intermediate-term goal is to focus on transforming my workflow such that I fiercely preserve time for the above class of activities. I want to get to a point where by default my days, weeks, and years contain sufficient investment in these activities, and underinvesting in them is a rare occurrence that triggers alarm bells and signals to me that something needs to change.

Of course, recall the gravity turn: getting from the surface of the Earth into orbit requires taking off in a direction perpendicular to the surface in order to avoid the bulk of the atmosphere, and only then gradually turning to approach the direction of orbit. Similarly, I need to allocate effort into ‘accelerating vertically,’ forging new daily habits, one stage at a time. I need to fight to free up slack, in my life and subsequently defend it from the consistent barrage of enticing opportunities to trade it away.

Moreover, reaching orbit requires more energy than the longest flight. Likewise, reaching academic orbit is more ambitious than any project I’ve undertaken so far. It’s hard to make a fundamental change to one’s life balance, and maintaining balance in the face of strong career incentives is likely to be even more challenging. This is not even to mention all of the other elements of academic orbit identified by Alkjash in the gravity turn essay. But, if I can pull this off, then maybe I have a shot at reaching the stars.